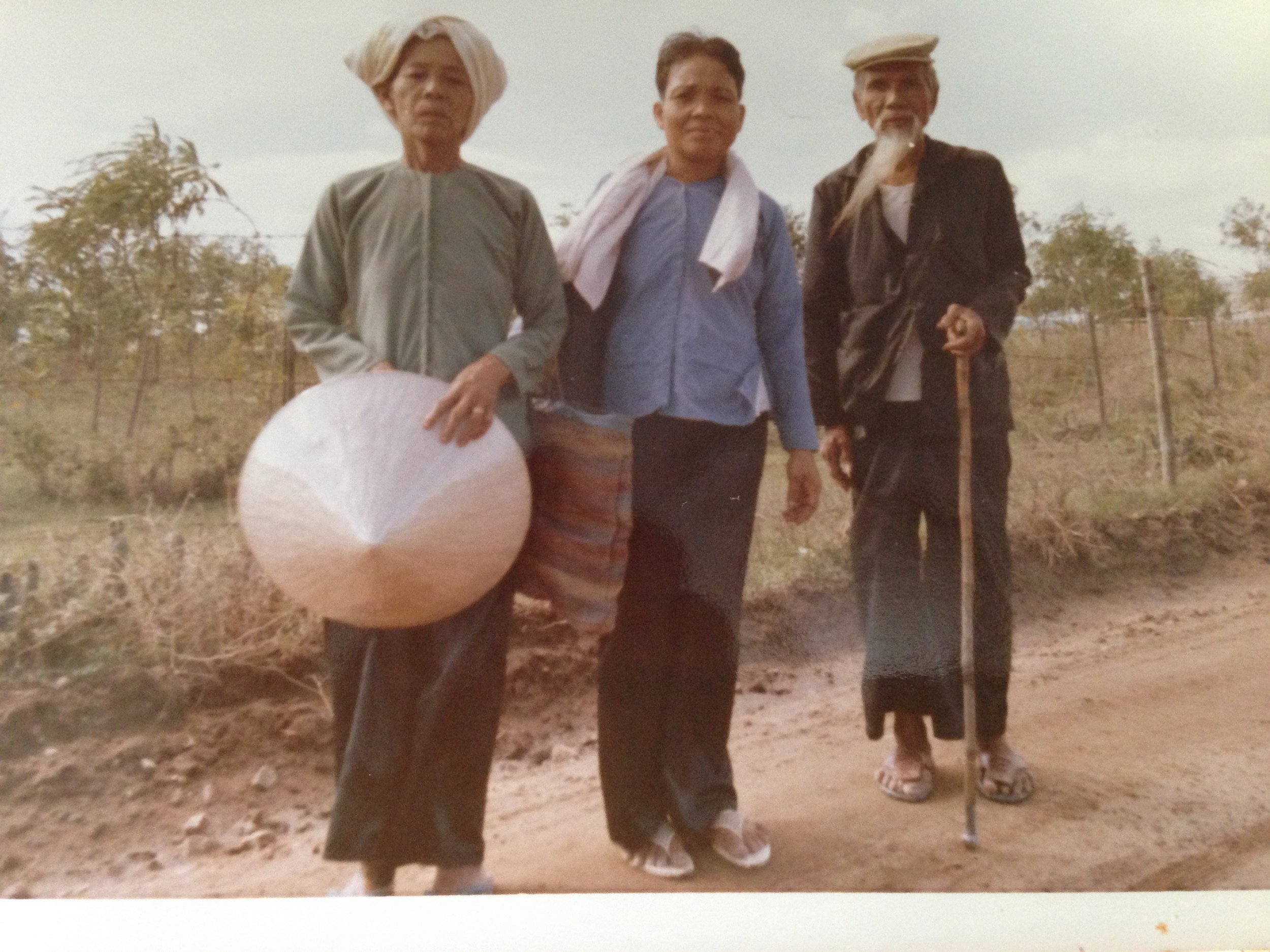

This is my second post about the enormous tragedy that the U.S. brought upon Cambodia by sponsoring the 1970 coup. My previous post recounted how “ethnic cleansing” followed the coup, dropping Cambodia’s Vietnamese population by more than two thirds within five months. Some 200,000 of these were forcibly sent to Viet Nam, and the 10,000 sent to Bao Loc, Lam Dong Province, saw me amidst the local Vietnamese extending a welcome and aid.

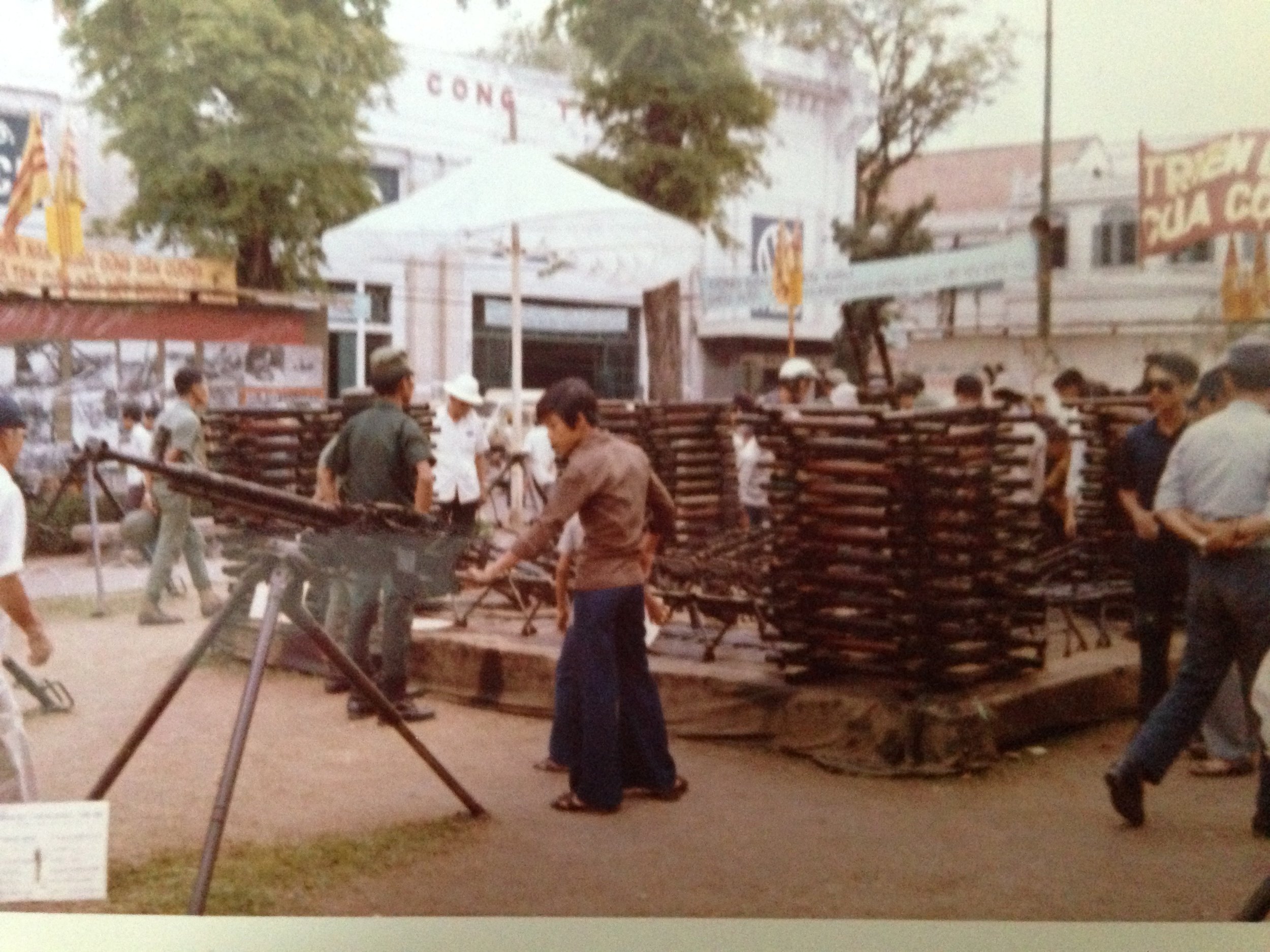

About a year later, I was on a TDY in Phuoc Tuy Province, advising the relocation of Vietnamese from the long-fought-over areas just south of the DMZ. While driving along a road that led to Vung Tau, I repeatedly saw two long lines of young men, all in identical bush-colored shirts, shorts and hats, and each carrying a rifle. They were not Vietnamese; they were Cambodians, being trained to join the existing cannon fodder in a cause that was hopeless from the start. I’m sure that every one of them was dead within a few years, if not months.

Nigh on fifty years later, it is this memory—of two rows of young men walking down both sides of the road, as far as my eyes could see—that remains the most vivid of them all in my mind. That’s because it has become more than just a memory; it has come to symbolize the whole bloody disaster that was our lot and our legacy.

How odd that I should find the symbol of all the useless, pointless death and suffering brought about by our involvement in Southeast Asia among Cambodians, not Vietnamese. My encounters with Vietnamese were extensive and prolonged (and usually conducted in their language), while the Cambodians were just “there” a few times. The Cambodians I encountered had no individuality; they were just young, smiling faces with flashing teeth, whom I passed by quickly, never stopping. Then one day they weren’t there anymore.

For me, these young men filling my windows on each side as I drove by symbolize the larger picture that we as individuals so often ignore: so many men—and uncounted women and children— on all sides, all sacrificed to myths, and all ultimately betrayed. Vietnamese, Americans, Cambodians, Hmong and so many others, both those who believed and those who were given no choice, not to mention those who just found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. The list is both long and diverse, a twentieth-century tragedy.

So many lives lost, so much treasure expended, and we Americans can take responsibility for most of it.

I relate this brief experience, my work with Vietnamese suffering “ethnic cleansing,” and the occasional events of just plain weirdness that compromised my two times “in country” in “A Spear Carrier in Viet Nam; Memoir of an American Civilian in Country 1967, and 1970 – 72,” available from McFarland & Co. or Amazon, in either book or Kindle formats.

By the book’s end, you’ll understand why its final paragraphs deal with my hopes for the unpleasant fate of Henry Kissinger in his already-too-long-delayed afterlife.

Thank you for reading this.